Maredsous Abbey School & Fernand Demaret Studio

Betty De Stefano

— Collectors Gallery

Belgian Modernist Jewellery, a journey

A few years ago, I fell in love with beautifully made 1960s Belgian jewels signed by Demaret and produced by master jeweller Claude Wesel. I was excited to discover their history.

I avidly researched for information, for stories that would allow me to understand its power. The more I learned about the works of Claude Wesel and the Groupe Atelier Demaret, the more I fell under the spell. I no longer had any choice; I had to put together a collection of these incredible pieces of jewellery, which were actually genuine works of art.

My desire to share my findings with others sparked the idea for this catalogue. I wanted to tell you all about the collaboration between a couple of Brussels jewellers and young artists goldsmiths, most of whom were students at Maredsous’ École d’Art des Métiers, and to share their unique journey with you.

I should like to express my deepest gratitude to Bernard François, goldsmith, gallery owner and teacher, who so generously shared his experiences and knowledge with me and without whom this catalogue would never have seen the light of day.

“Fantastic jewellery for people who are slightly mad”

Catalogue published in 2022 - Brussels - Edition Collectors Gallery - ISBN 9782960306309

FROM ABBEY TO GALLERY,

THE TALE OF THE GROUPE ATELIER DEMARET

MAREDSOUS

Introduction

In 1960s Belgium, a beautiful artistic tale began. A group of talented young goldsmiths and a couple of Brussels jewellers met to form an ephemeral artistic movement, the Groupe Atelier Demaret. Together, these artists created a plethora of jewels combining baroque and abstract styles, and authentic and bold sculptures. These incredible artists’ pieces of jewellery still enchant us today.

The world was changing drastically, skirts were getting shorter, and colours sparkled. A more traditional school – at least on the surface – blew a fresh breeze of freedom over the world of contemporary Belgian jewellery and gave it its most outstanding artists. None of this would have been possible without the École de Métiers d’Art de l’Abbaye de Maredsous (school of artistic crafts of the Maredsous Abbey) which played a pivotal role in this story and from which all of our heroes originate.

60 YEARS OF CREATIVITY

In 1881, the Collège Saint Benoît was founded in the shadow of the Benedictine abbey of Maredsous, erected nine years earlier. A few years later, the Abbott Hildebrand de Hemptinne, who was passionate about art, recommended training young people from underprivileged backgrounds in manual crafts. The idea was later embraced by Pascal Rox who opened the École Saint-Joseph on the site with a class of nine students in 1903. The curriculum focussed on providing pupils with a general education together with a high-quality apprenticeship in crafts. The school quickly grew and, in 1908, it opened a casting workshop and a drawing studio.

From then on, the Benedictines ran the school with an emphasis on arts and crafts training and avoided the temptation of opening the school to a more individualised artistic training. After the First World War, Célestin Golenvaux introduced production workshops headed by artisans who had trained there previously. These men excelled in goldsmithing, enamelling and cabinetmaking, while the bookbinding and embroidery departments, which were more closely involved with the creation of liturgical objects, were abandoned. Orders poured in and spurred on the creativity of the teachers, the most dynamic of whom was undoubtedly the designer Sébastien Braun. With these teachers, the style evolved towards modernism, which dominated the interbellum period. While this chapter of the school’s history was marked by innovative enthusiasm, the subsequent period under the guidance of Laurent Matthieu was dominated by a more orderly structure, but one still driven by talented craftsmen who continued to reject any artistic productions that might reflect individual talent. As of 1939, a new headmaster Ambroise Watelet sparked a genuine school spirit underpinned by many outside cultural activities, trips, exhibitions and meetings. There were only forty boarding students living at the school “as a big family” in a cosy atmosphere as they enjoyed close working relationship with their teachers. However, the ideologies whereby artistic creation should be dismissed in the interest of craftsmanship became difficult to maintain as many students were regularly approached by a demanding clientele requesting personalised items. In the early 1950s, Father Anselme Gendebien officially changed this programme and many artists graduated from Maredsous – including sculptors Félix Roulin and Emile Souply – having produced very beautiful pieces of jewellery. Henceforth, the school enjoyed a genuine international recognition, boasting about fifty students and a ceramics workshop.

In 1958, the architect Grégoire Watelet was appointed to run the school and started initiating international partnerships, most notably with the Swiss Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts). As an undisputed expert on Art Nouveau – and particularly on Gustave Serrurier-Bovy – the Abbott Watelet and his team encouraged freedom of expression and creativity for everyone, to the extent that the school progressively acquired a rebellious and anti-conformist image that would progressively amarm the ecclesiastical authorities. The adventure of this remarkable school of arts and crafts culminated in 1964, when Maredsous merged with Namur’s Institut des Arts et Techniques Artisanales (IATA), the heir of a creative mindset, innovative teaching methods and a legacy that has marked several generations of craftsmen and artists.

— Diane Hennebert

Maredsous, the Advent of the Creative Artisan

This is where it all began. In the magnificent setting of the Abbey, this celebrated school devoted to the arts and crafts has trained the most acclaimed gold and silversmiths and cabinetmakers in Belgium for the past half-century. As the Second World War raged, the school embarked on an academic revolution that would change the Belgian artistic landscape forever.

Since its inception, the school has had but one motto: “learning to execute”. While it trained talented craftsmen, it formally prohibited personal creation. Whereas the outstandingly talented cabinetmakers and goldsmiths gave the churches a golden glow and middle-class interiors a distinctive sparkle, the Maredsous students’ notebooks did not feature a single original piece of art.

But the arrival of one man would change everything. In 1939, Father Ambroise Watelet became the school’s headmaster, and, in the space of a few years, he ushered the school into a new era and reassessed the traditional approach to craftsmanship hitherto espoused by Maredsous. As far as he was concerned, technical knowledge was both the foundation and the instrument of artistic creation. The traditional perception of the artisan is outdated, and a new profile emerges: the artisan-creator. Henceforth, the training provided will be concurrently technical and artistic.

Teaching staff

The Craftsman-Artist

Modern life and secularism found their way into the century-old walls of the Abbey. Art, music and photography classes were held between the foundry lessons. The faculty grew and evolved, and artists started teaching at the Maredsous school. From then on, the students’ artistic flair was encouraged and honed along with their technical skills.

In 1958, Father Grégoire Watelet – an architect who also taught art history – initiated a rapprochement with Zurich’s School of Arts and Crafts, the Kunstgewerbeschul*. This initiative injected a spirit of modernity into the Abbey. The Bauhaus soul entered into a dialogue with religious art, and a brilliant generation of students became imbued with the world surrounding them.

To encourage the students’ budding artistic sense, the school hired several talented artists such as Marcel Warrand, artist painter who taught drawing (study of colours and shapes) and sculptor Félix Roulin who taught casting (forms, visual). Consequently, artists recognised in this unique discipline started emerging from the ranks of the institution, which had never offered a specific jewellery-making class. Emile Souply, Félix Roulin, Raf Verjans, André Lamy, Didier Gogel, Claude Wesel, Bernard François and many others followed. The spirit permeating the school, its technical specifications, its receptiveness to creativity and modern artistic expression, all contributed to the emergence of a number of artists who not only left their mark on the world by practising the art of jewellery in their own original style but who also communicated their passions to others through their teachings. In turn, students who became artists started teaching.

Unfortunately, in 1964, the school was forced to shut its doors. Training continued at the École des Métiers d’art, in conjunction with the École artisanale de Namur I.A.T.A. (Institut des Arts et Techniques Artisanales, the Institute of Arts and Crafts Techniques).

As they made their first steps in the professional world, the young goldsmiths who had graduated from Maredsous were frequently confronted with a shortage of opportunities. The austerity policy stemming from the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) had accelerated the demise of the market for religious artefacts. The order books of the workshops dwindled, and “extravagant” pieces became an oddity.

This is when Fernand and Eliane Demaret entered the scene.

Teachers & students of the Maredsous Abbey School - year 1961-62

The Maison Fernand Demaret

In the 1960s, jewellery design broke away from the mainstream and shifted towards abstraction. Shapes “melted”, and standards changed. Jewels became works of art and ornaments. A distinction appears between artist’s jewellery and handcrafted jewellery.

It was around this period that Fernand Demaret (1929-2013), who was born into a family of silversmiths in Namur and schooled in his father’s workshop by his uncle, chose to perpetuate the family tradition, albeit in Brussels. But he was not alone in this adventure. The role played by his wife Liliane Nathalie Mosselmans proved pivotal. As a genuine pioneer, she was intent on opening the city’s most beautiful boutique where she would sell high-quality contemporary jewellery. Unique and never-seen-before jewellery!

The Demaret Jewellery store in Brussels was located rue du Bailli, 10 from 1961 until 1968, than moved to prestigious avenue Louise, 31 from 1968 until 1995. From 1995 to 2013, Fernand Demaret attended customers on appointment rue du Bosquet, 31 (workshop and show-room).

As an art lover, Mrs Demaret never tired of tracking the best young artists, to whom she offered exceptional conditions for creativity : precious metals, fine stones, and pearls, which they could in turn use in complete freedom.

Whilst the objective remained commercial, the design of the jewellery increasingly became contemporary. Less standardised, the object becomes an artwork.

Jewellery Sculptors

In 1961, until then, influenced by the great Inca and pre-Columbian civilisations, the Demaret couple hired a former student of Maredsous, André Lamy.

This collaboration laid the cornerstone of the Groupe Atelier Demaret.

Some years later, in 1963, the workshop expanded with the arrival of Claude Wesel, who also trained at the prestigious Maredsous school. His collaboration with André Lamy and Fernand Demaret resulted in unique jewels studded with pearls, opals and cabochon encased diamonds. Together, they designed collections combining abstract and organic forms. The Demaret style was born.

In 1967, Michel Louwette joined the group. His simpler style was completely in line with the Demaret house. One year later, Bernard François would improve the style once again, when he started working the metal – in this case, gold – directly, hammering and carving it to shape it to match his own inspirations.

The balance between technique, a constant focus on quality, and creative ideas is central to their approach.

They design and manufacture the jewellery themselves, controlling each phase of the process. There are no creators and craftsmen, no thinkers and doers. Using the lost wax technique, they invent abstract and organic creations worn as jewellery.

The Demaret style would pave the way for a free and inspirational production, with one guiding principle: imagining jewellery reflecting its wearer’s personality.

Groupe Atelier Demaret

Over time, the Demaret jewellery shop evolves into a gallery, showcasing a “modern style”, that embodies its brand image, both in Belgium and abroad. The collections are presented to the public in a sumptuous shop, where throngs of visitors flock to the previews as though looking at works of art.

The name Groupe Atelier Demaret first appears in the late sixties. The group consists of Fernand Demaret and other young artists working in the studio, including André Lamy, Claude Wesel, Michel Louwette, Bernard François and Maurice Toussaint. The brand becomes a reference in the world of modern jewellery, and the group’s pieces are displayed in Belgium, Japan and the United States, from New York to Dallas. Following a global movement that challenged the traditional world of international jewellery, the group of artists presents original pieces, which were not only conceived but also made by their creators.

In a little over a decade, the world of artist’s jewellery made a dramatic leap into the modern world. Artists such as André Lamy, Claude Wesel, Michel Louwette, and Bernard François removed the boundaries between sculpture and jewellery.

In the early 1970s, Bernard François, Maurice Toussaint, Michel Louwette and Claude Wesel all left Demaret and went on to create their own pieces of jewellery with great talent and success. Meanwhile, Fernand Demaret continued to create and sell jewellery in Brussels’ finest jewellery store. A page is turning ...

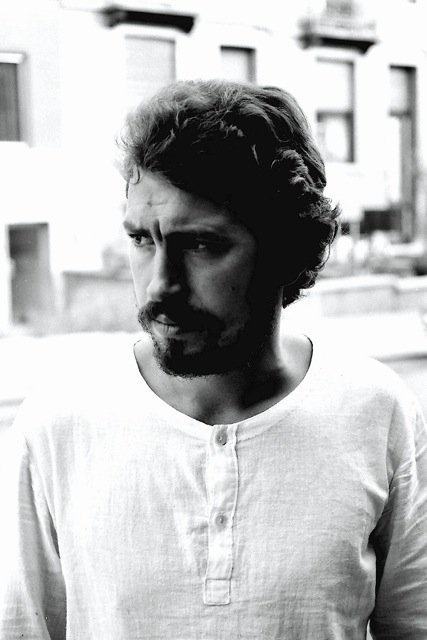

Claude Wesel, Michel Louwette, Fernand Demaret, Bernard François & Cesar, the dog at Fernand Demaret’s workshop - in Brussels, Boulevard du Souverain

CONVERSATION WITH BERNARD FRANÇOIS

— A major witness in the world of the artist’s jewellery

Bernard François recounts an era that left its mark on the world of jewellery forever.

Regarded as one of the most important figures in contemporary Belgian jewellery, he is simultaneously a goldsmith, visual artist and gallery owner and produces colourful, avant-garde pieces using industrial and technological processes. Having grown up around his father’s tool factory, he was instinctively drawn to a career where he could harness the material and was captivated by metal. In the mid-1960s, he was among the six artists of the Groupe Atelier Demaret, which left its mark on the emergence of modern jewellery in Belgium.

COULD YOU TELL US ABOUT YOUR TRAINING IN THE ART OF JEWELLERY?

I did not train as a jeweller but as a goldsmith. When I was young, there was no such specific training in Belgium. I learned goldsmithing at Maredsous’ École de Métiers d’Art. This profession opens up infinite possibilities; its techniques are very versatile and can be used in other disciplines. The methods are the same: beating, restraining, hammering, chiselling, engraving, setting...

You mustn’t think of the object or its purpose. You have to think about the techniques involved, because they all enable you to work the metal, regardless of the purpose of the object. In jewellery, we expand the debate between the object and the body.

It was not until the final year that our studio teacher allowed us to work specifically on jewellery. After leaving Maredsous, once I was at La Cambre, I started doing some research focusing on jewellery.

HOW DID YOU END UP AT THE MAREDSOUS SCHOOL OF ART?

When my parents were young, they had friends who used to come back home beaming with the sheer pleasure of being at the Maredsous school. This stuck in their minds and when they realised that the so-called traditional education was not for me, they remembered this. I had already had a short introduction to design – and more specifically to the “Scandinavian school” – in a Parisian gallery exhibiting furniture, objects and jewellery. But at first, I had no idea that I’d like to make jewellery. I was only 16 years old, I was good at drawing, like any other child, but that was it. During the summer holidays, my parents took me to visit the school: initially, I found the surroundings, the facilities and the abbey enchanting and took the entrance examination informally. Marcel Warrand asked me a few questions and instructed me to make a drawing. I cannot remember the theme... They probably sensed that I had some kind of talent because that was enough. Later, I learned that the first year was spent choosing which section you’d enter. I was immediately enthralled and instantly understood that this would be the key that would unlock every door.

TELL US ABOUT THE FAMOUS MAREDSOUS SCHOOL.

I arrived quite late after a great period of change. A few years earlier, the school management had already begun to bring in artists – some of whom were former students – to add a more artistic perspective to the curriculum in addition to the purely technical training. We had extraordinary teachers. Artists who conveyed new ideas, such as former student Félix Roulin, for instance.

For his part, painter Marcel Warrand taught us to open up, to look at things and to draw more freely. All these artists taught us additional skills: drawing, decoration, colours, casting, “the third dimension”.

I would argue that these courses became more important to me than studio work. In the studio, we worked from our own drawings, learning to make plans, technical drawings, but the art courses enabled us to develop a sense of design and of research. More than teaching us a job, there was an intellectual openness in these courses that gave us the ability to create, that stirred our imagination. It was a unique experience.

Since I enrolled in Maredsous in 1960 only four years before it closed its doors in 1964, I was there during the last years of the school. I had to spend my last year at the École Artisanale de Namur, and this proved a very different experience... I often go back to the Abbey; it still exerts an irresistible attraction...

“There was an intellectual openness (...) that gave us the ability to create, that stirred our imagination (...)”

YOU STILL SEEM VERY FOND OF THE SCHOOL, EVEN NOW. WHAT WAS SO SPECIAL ABOUT IT?

It was a religious school, and a boarding school at that, but it was extremely modern and open to the world. We were only 50 students, all sections combined, in an abbey set in the heart of the forest. There was a family atmosphere deeply rooted in harmony and freedom. It was the ideal place to thrive. As there were teacher exchanges with other countries, we were taught by teachers from the Zurich School of Applied Arts, the Kunstgewerbeschule. The story of Maredsous is essentially a tale about people.

SO HOW DID YOU END UP WORKING FOR FERNAND DEMARET, AFTER HAVING BEEN TRAINED AS A GOLDSMITH WITH A RELIGIOUS OUTLOOK?

In the mid-1960s, the silverware industry suffered a strong decline. Fashions had changed, people no longer wanted to decorate their homes with large pieces, and most importantly, religious silverware underwent a great change. The notion of “excessive pomp” in liturgical objects had vanished. After Maredsous, I enrolled at La Cambre and immediately started looking for work upon leaving. I knew Claude Wesel and Michel Louwette from our days in Maredsous and La Cambre, and the first door I pushed open was Demaret, where they both worked.

AND SO, YOU JOINED THE ATELIER DEMARET GROUP?

It all started when Liliane Nathalie Mosselmans – Fernand Demaret’ s wife – met André Lamy, who was also an old friend from Maredsous. André started producing pieces for Demaret; he would work from home and would come to the shop to deliver his creations.

Then Claude Wesel (who had been in Maredsous a year before me), joined the Demaret workshop and shortly afterwards, he was followed by Michel Louwette. And finally, I joined, but only for two years.

The name “Groupe Atelier Demaret” was coined for an exhibition held at Brussels’ Théâtre National, “Art et Bijoux”. We carried on using it for our exhibitions abroad, in the United States and in Japan.

DO YOU FEEL THAT THE ATELIER DEMARET DESIGNERS HAD THEIR OWN PARTICULAR STYLE?

No, not really, everyone contributed creatively. We all had carte blanche. That was our contract, Fernand Demaret provided the studio, along with the gold, the stones and the pearls. Sometimes we worked on commissions, for clients who had “ideas”, but most of the time we were free to make our own designs. There was a prevailing method: the “lost wax” technique. But it’s true that when customers walked into the shop, there was a certain distinctiveness in the pieces proposed: yellow gold, the “matity”, a patina obtained from a magic immersion into a secret recipe.

CAN YOU TELL US A LITTLE MORE ABOUT THE “LOST WAX” TECHNIQUE? WHY IS IT SO SPECIAL?

This technique dates back to Antiquity but had been somewhat forgotten in our regions. Fernand Demaret revived it with a new vision for artists’ jewellery rather than moulds for large-scale reproduction. The form is built by adding a thin layer of wax which is soldered, just like metal. Then it is encased in a mould where the metal will be cast. The wax is burnt off and then replaced by gold. Demaret wanted to use gold. To be perfectly honest, I wasn’t too fond of lost wax and quickly realised that I would much rather work directly on the metal, the raw material. Gradually, others tried it as well and realised that it was possible to work the material directly. But lost wax was always there...

TELL US ABOUT CLAUDE WESEL?

Claude Wesel’s aesthetics were closely linked with lost wax. He had developed his personal style with his own language. His pieces made using the lost wax technique had the same finesse as when he worked the metal directly. He was the designer who worked the longest in the Demaret workshop.

“In jewellery, we open up the debate between object and body.”

WOULD YOU SAY THAT THIS PERIOD WAS PROPITIOUS TO THE EMERGENCE OF A NEW MOVEMENT?

In those days, everything coexisted, and the world was starting to open up. We were fortunate to have met artists through our schooling who pointed us in the right direction whilst allowing us to explore our own ideas. At La Cambre, for instance, we were steered from goldsmithing to sculpture. To sum it all up, it’s all a question of alignment. There was a combination of events, encounters, the same school, and then the same studio. And we were part of a worldwide movement, modernism in an era that recognised the creation of jewellery as artworks.

AFTER DEMARET, DID YOU GO ON TO WORK FOR ANY OTHER JEWELLERS?

I received commissions from Wolfers, Gardin, and other jewellers, as well as many private orders. I also worked for Polomé in Charleroi from 1971 to 1986.

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

I left Demaret in 1970 and together with Claude Wesel and Michel Louwette, we set up our own design studio. Most importantly though, I picked up my research, which had been shelved since La Cambre and my work in Félix Roulin’s studio. I started working with other materials, including stainless steel, aluminium and plexiglass.

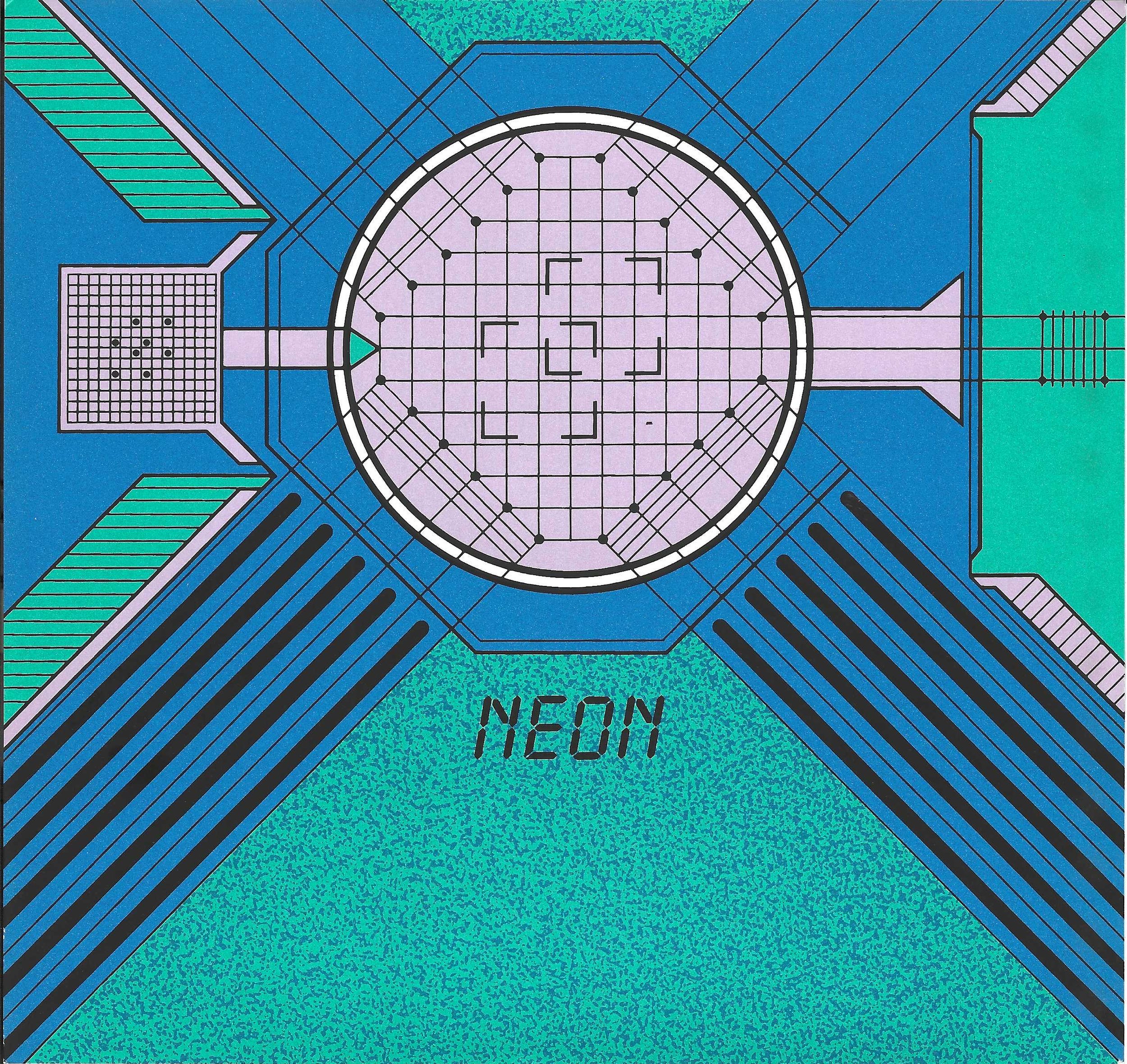

The journey continued with the opening of the NEON gallery-studio in 1975, which was a multi-disciplinary exhibition space. And I never stopped…

Brussels - NEON gallery

At the NEON gallery-studio, Bernard François decided to present the work of artists who ventured off the beaten track of design, rejecting the idea of confining jewellery inside a box. This centre for the revival of modern jewellery, which provided an exciting playground for experimentation, offered creative artists an ideal opportunity to expand their horizons internationally and to confront their work with new materials. Over several decades, the NEON gallery functioned as a laboratory for Belgian and international creation, where all types of art forms – sculpture, drawing, silk-screening, etc. – were given a unique place where their influence is still felt today.

From 1978 until 2008, Bernard François at Neon Gallery exhibited more than 250 artists.

A major retrospective multidisciplinary exhibition, Bernard François. Autour du bijou, was held by the Goldsmiths’ Museum of the Château de Seneffe from 09.10.2018 to 31.03.2019.

A TREND THAT REASSESSED EUROPEAN JEWELLERY DESIGN

During the first half of the twentieth century, gemstones gained the upper hand over metal, and jewellery design took precedence over metalwork. This shift came as a response to the considerable advances in the art of gemstone cutting and setting. In the early 1950s, some designer- jewellers who were still bound to the tradition of goldsmithing and sculpture lamented the fact that the setting was becoming anecdotal. In the 1960s, however, a radical new vision of jewellery appeared under the aegis of a group of young jewellery graduates who began questioning the metal/gemstone equation. In an attempt to tackle the third dimension, a number of schools, workshops and independent designers across Europe began exploring new approaches in Italy (the Padua School) Scandinavia and our dear Belgium with its École des Métiers d’Art in Maredsous.

A REVOLUTION IN THE TEACHING PROGRAMME AT MAREDSOUS: CREATIVITY JOINS FORCES WITH SKILL

Maredsous spawned many different artistic personalities, each with their own unique expression as strong links were forged between teachers and students. These creative jewellers and goldsmiths – indeed, there is no point in attempting to distinguish the two professions – have all chosen their own path. And yet, with the benefit of hindsight, we can now identify them as the “Maredsous School”.

This particular group of people gave birth to “Belgian jewellery”, and, in 1987, Dominique Minet, director of the Ateliers d’Art, wrote: ‘Jewellery is no longer just an object for investment or speculation; it has become simultaneously art, science, and technique. In this way it has found its identity: Belgian jewellery exists.’ Here are its shared principles: values are in turmoil and the notion of “precious” shifts from traditional materials to the artistic approach. The preciousness ‘traditionally attributed to gold, platinum and gemstones’ leaves the exclusive club of noble materials to invest the soul of the so-called “humble” materials.

Yet, some of these artists, including Didier Cogels, Claude Wesel, André Lamy and Fernand Demaret, still favour noble metals such as gold and silver for their workability. In this sense, they fall in line with the trend set by Scandinavian countries, turning their research to pure forms and new textures.

The lost wax technique, which has been used since ancient times, allows these young designers to explore new forms and multiple effects with their material of choice. This process enables the extraction of the most fantastic shapes with great ease due to the simplicity of the wax carving process. The resulting shape is then encapsulated in refractory cement and then cast in metal, the latter replacing the wax melted under high temperature. Once removed from the mould, the jewel is then set, chiselled and polished. Goldsmiths and jewellers are therefore perfectly able to manipulate the metal and play with its shapes and colours.

CONCLUSION

A jewel always reflects its own era. The artist-jewellers of the 1960s embraced technological breakthroughs, space travel and the sexual revolution. Although Belgian jewellers and designers never sought to be associated with a specific movement, their training brought them together, despite themselves, and they developed a style that could be described today as the “Maredsous School”, which is characterised by jewellery that rivileges metal work over the use of stone, which remains secondary. Metal is crushed, folded and printed. The lost wax method dominates.

In their approach, these designers are all very rigorous. Indeed, meticulousness is the most important quality required by working small pieces. The high level of technicalities and abstract motifs can express, in spite of themselves, a degree of “masculinity”, which is very different to the romanticism of some eras.

A 1982 exhibition in London entitled Redefined Jewellery bears witness to the internationalisation of the transformation of the vision of designer jewellery in which Germany, Great Britain and the Netherlands were all involved. The aim here was to redefine jewellery along the lines of miniature sculptures.

With its renowned École de Maredsous, Belgium can proudly claim to be among the international avant-garde jewellers of the 1960s and 1970s.

The words of Claude Wesel perfectly encapsulate this approach: ‘... isn’t true creativity about evolving rather than disavowing the achievements of the past? Simply to be ahead of those who are behind.’

— Laure Dorchy

“‘Jewels are amongst the first messages that humankind received from the world, objects of art that should be exhibited on the body. Jewellery reflects an era, a society and a culture. My entire creative process can be explained using two examples grapes and bubbles. On the surface, the two are unrelated, unless the creative sublimation happens to be Champagne! My role consists in fulfilling them and organising this chemistry between the spirit and the medium.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Le bijou contemporain

Bijoux belges contemporains

Pierre Paul Dupont et Johan Valce,

Ed Mardaga, 1992

EXHIBITION CATALOGUES

Maredsous, art du bijou, bijou d’art

Exhibition catalogue. Centre Grégoire Fournier

(formerly l’École des Métiers d’art de Maredsous)

May - August 1987

Gioielli di artisti belgi dal 1900 al 1973

Catalog Exposition at Museo Poldi Pezzoli Milan, Italy

(november 7 - 20, 1973)

INTERVIEWS

Fernand Demaret Le 18 juin 1997

Claude Wesel 1997

Claude Wesel, a true creator and visionary

“Claude Wesel is first and foremost an accomplished jeweller in spite of having sometimes expressed the desire to work on a larger scale and become a sculptor. He favours complex assemblages, opposing or uniting shape and line, often with a unexpected boldness, always with remarkable mastery. He is also an accomplished craftsman for whom few jewellery techniques hold any secret. Lost-wax casting, stone of pearl setting metal fabrication, sensitive use of coloured acrylic, nothing leaves him unmoved, Recently, he successfully rediscovered organic materials such as lizzard skin, tortoise-shell, ivory, amber or ancient techniques such as enamelling. When using precious or semi-precious stones, he makes them the focal point of his construction; all the shapes, lines and colours are arranged in relation to the stone so as the enhance its sparkle. To quote him: “the diamond’s exceptional decorative value stems from its great power of refraction.... it is used for its beauty, not as a symbol of wealth, it can still form an integral part of an accomplished work of art”.

The end result is often a sumptuous form of ornament whose boldness of shape and line recalls today’s world of space exploration. Conversely. Claude Wezel also looks for inspiration in the natural world of plants and animals, which he transposes, synthetises into a mechanical and abstract language.”

Bijoux Belges contemporains. Ed Mardaga, 1992. Page 67.

His elegant pieces combine simplicity and complexity with audacious lines. Often based on nature, his compositions translate plant and animal forms into an abstract language which some have described as biomechanical. The light is captured in a clever combination of matte and shine or appears trapped in diamond and pearl cocoons. From 1960’ on, he designed more than 10 000 projects of jewels. His exceptional production in terms of pieces and quality will forever mark the style of the Demaret house.

“People sometimes refer to me as an avant-gardist, but this is a simplification of the label, I prefer the word timeless or universal.”

“... Bringing technique to art through my processes and art to technique through my inspiration, is my quest as both man and artist.”